By MAURITS LEEFSON

How to Avoid Nervous Breakdown in Pianoforte Playing

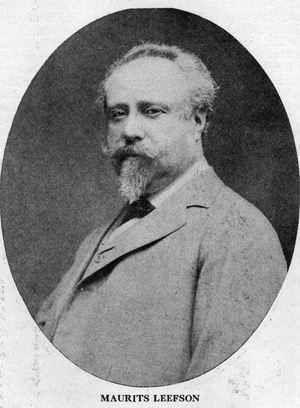

Biographical

Mr. Maurits Leefson, well-known piano pedagog, and editor of musical works, was born at Amsterdam, Holland. His father, grandfather and many of his relatives were musicians. He commenced the study of the piano at the age of six, his first teacher being his father. He secured a free scholarship at the Amsterdam Conservatory. Among his teachers were Van der Eyken and Daniel de Lange. He then went to the Cologne Conservatory where he was a pupil of Ferdinand Hiller and Isidore Seiss. He came to America in 1887 as a choral and orchestra conductor. His success as a teacher, however, led him to devote his entire time to that profession. Among his pupils have been several students who have won the first prizes in national contests, including that of the American Federation of Musical Clubs.

“HAVE you ever seen a musical, nervous breakdown? The music world is full of them. They are people who have struggled with all their might and main to acquire a beautiful and noble artistic project, but who, afterwards, find themselves becoming more and more impotent with every step.

“HAVE you ever seen a musical, nervous breakdown? The music world is full of them. They are people who have struggled with all their might and main to acquire a beautiful and noble artistic project, but who, afterwards, find themselves becoming more and more impotent with every step.

“Surely music itself does not do this. Music is believed to have a beneficial effect upon the nerves; and I agree with this. Otherwise, why would mothers croon their children to sleep. Work of the right kind does not cause the breakdown; because hundreds who have worked very hard are able to reach their goal.

“Of course, the breakdown may be due to ill health, wrong diet, too much excitement, too much worry and many other causes; but I find that most breakdowns in piano study are due to one thing and one thing only, and it is with the hope of remedying this cause that I am writing this article for The Etude.

“The thing that causes nervous breakdown is the strain upon the nerves caused by badly prepared hands. After thirty-five years of teaching and the observance of thousands of pupils in the conservatory of which I have been the director, I have come to the conclusion that this condition is far more serious than most teachers imagine.

A Rational Cure

“FORTUNATELY, the cure is a perfectly rational one and within the reach of all. It is no ‘quack’ remedy and there is nothing proprietary that one has to purchase.

“It is the prime duty of anyone who teaches piano to ‘make’ the hand of the pupil as near as possible come toward that of the ideal pianistic hand. This is particularly the case with students who have obvious shortcomings, such as very stiff fingers, double joints, flabby hands, and other physical shortcomings. There is no use in expecting these things to remedy themselves as the regular teaching work goes on. They don’t. They usually grow worse and often entirely impede the work of the student.

“The exercises which I will give are remedial in all directions. They may be applied with or without a teacher. A fine teacher, however, is always desirable. It is usually far easier and requires less time and effort to make a stiff hand flexible than to make a soft, flabby, jelly-like hand solid, yet resilient.

“It takes me about six weeks to ‘make’ what I call a pianistic hand. Of course, that is only the beginning. What I prescribe may be used by any teacher, as it is based upon very slow and detailed attention to the development of the fingers. The secret of the work is slow, continual progress as opposed to jumps ahead. If the reader were asked to lift a two hundred pound weight, he would probably find it impossible; but if he were trained every day, starting with a one pound weight, he would in the course of time, be able to lift two hundred pounds or even more.

“The evil of most teaching is that the pupil is permitted to rush into his work with no previous training. He is permitted to start in with fifty or seventy pound weights, as it were. People have often commented upon the security and ease with which my pupils have played while under the nervous strain of the prize contests. This self-possession has been carefully built up through years by just such methods as I shall describe in more or less detail in this article.

Getting the Groundwork

THERE is nothing arbitrary or proprietary about the means I employ. I beg of the reader to try to get the principle of the thing and not to imagine that any set exercises which cannot be varied are indispensable. In the first place, I feel that some two weeks of preparation apart from the piano are desirable in making a pianistic hand. If the pupil is a very little one and it is needful to keep up the interest, it may be necessary to prolong this period, but at the same time, juvenile methods of teaching notation may be employed and the pupil may be entertained by listening to music. No time is really lost by this. In fact, a great deal of time is gained.

“One of the first goals is to see that every finger of the hand is trained equally well and by the same method. The first exercise I employ is to let the pupil rest his forearm and hand (palm downward) on a table at such a height that the arm rests comfortably on the table.

“Then I show the pupil what we are working for. This is most important. The pupil must, above all things else, have the right mental concept. Why? Because, most of his work will be done at home where you cannot observe his practice; and he must be told that he is at such times the sole and only teacher. How good a self-teacher he becomes will determine how rapidly he will progress in the right direction.

“In order that he may understand the main principles of muscular and nerve control, I illustrate on the table. Placing my own hand in correct playing position, I raise the second finger, as do many students, with a nervous tension governing the motion. The student sees the finger tremble—he watches this delicate nervous tremor. This, I tell him, is the thing of all things, in all his piano playing all his life, that we must avoid through proper training and practice. If this lack of muscular control is permitted to develop in the slightest degree, it is sure to progress like a disease. The culmination of this disease is pianistic nervous breakdown. I have never known it to fail. No student can continue to play with this tremor and hope to appear in public with confidence and success. This is so important that I could write volumes about it. It seems like an insignificant thing and there are thousands and thousands who have permitted it to develop through their entire careers and still wonder ‘why they cannot play.’ In such cases, the hand has to be made over again, by just such methods as I am describing.

“After the pupil, young or old, has become thoroughly convinced of the original sin of this nervous tremor, I next show him that, if his finger does not tremble, he has real nerve control and that which also leads to in dependence of the fingers, a really very great desideratum as every teacher knows. It is difficult to bring this matter of independence to the pupil’s consciousness. One of the best means is by kinaesthetic methods. That is, let the pupil feel on his own skin what is really meant. I place my own hand in playing position on the top of the pupil’s hand. I raise the third finger to striking position. In doing this, I imitate what most pupils do when they have not mastered the real spirit of finger independence that is, as I raise the third finger, I depress the adjoining fingers, the second and the fourth fingers.

Individual Action

“INDEPENDENCE means individual action. It means that one finger is to move; it must move by itself and not move any other fingers with it, or with any assistance from the other fingers. If the fourth and second fingers of the hand go down when the third is raised, none of these fingers is working independently. The pupil feels this by feeling the weight of my fingers on the back of his own hand. He is immediately impressed. Then I repeat the same demonstration, this time, however, raising the third finger without permitting the second and the fourth fingers to press down on the pupil’s hand. Again the pupil grasps at once the true meaning of finger independence. Unless he has this idea in his own head, no amount of pedagogical preaching will give him the right idea of finger independence.

“The pupil now has two governing principles which must rule all of his playing. The principle of making finger motions without tremors or trembling and the principle of playing each finger with the independent feeling. His arm and hand have been lying on the table all this while and are naturally relaxed. His next direction is to move the thumb under the hand—and this is followed by raising the fingers to their tips on the table. This usually approximates the playing position. If it is not right, I correct it.

“Then I place my hand in the playing position and raise the third finger (it being the strongest and easiest) very, very slowly. I tell the pupil that this very slow ascent is most important, because in this way he can avoid the forbidden tremblings. I ask him to imagine that a slow moving picture of the hand is being taken. If the finger ascends in jumps or jerks the whole process is wrong. Here the teacher’s patience comes in; and it takes real patience to get the right result. Very few pupils, indeed, can make this initial motion without jerking the finger up instead of moving it up very slowly.

“In working out the exercise, the pupil is instructed to count four as the finger ascends, count four or even more, rhythmically, as the finger is held aloft, count four as the finger descends. The metronome can be used to advantage, but is not indispensable. The pupil should be cautioned continually that there is nothing in the exercise itself that produces unusual results. The important thing is how it is done. For instance, when the finger is held aloft during four counts, in nine cases out of ten the teacher cannot see with his eye that the finger is being held in a strained position. How can this be overcome? The pupil must be taught some means of determining this for himself. I, therefore, have the pupil take the thumb and forefinger of his own hands and grasp my hand on each side of the third finger so that he can feel the flesh, the web-like skin between the fingers.

“Then I raise my third finger properly. He does not notice any strain. However, if I raise it just a little too high, the strain is immediately noticeable to his touch. The pupil then comes to know that there is a point in raising the finger above which he dares not go without dangerous strain.

“Occasionally, the teacher will encounter a pupil with an arm that requires further treatment for relaxation. With such an arm, I take the pupil’s finger tips with both of my own hands and, by an upward and downward motion, swing the pupil’s arm until it becomes entirely limp from the finger tips to the shoulder. This must not be done too violently, of course. This motion of swinging the arm is not unlike that used by the candy-maker when he swings a long strip of candy hanging from a post.

“One of the most interesting discoveries I have ever made in connection with piano students, who play pieces that are too difficult for them, is that the point of greatest contraction or tightening seems to be in the shoulder. The arm may seem fairly free but the shoulders are so tight and so hard that they seem to be riveted to the body. The exercise I employ to correct this is to direct the pupil to stand at ease and at count one, to let the shoulders flop down as if they were very tired. While counting two and three they remain in this position; at count four, however, they are elevated high. Then the exercise is repeated several times. The main thing is to ‘let go’ of the shoulders and let them drop completely at count ‘one’ and to keep them completely relaxed for the next two counts.

“The next corrective exercise for shoulder contraction is to stand at ease; at count one throw the shoulders back, at two let the shoulders relax forward and keep them in this relaxed position while counting two and three. A variant of this is to throw the shoulders far forward, on the count one, relax them on counts two and three, and then throw them back on count four.

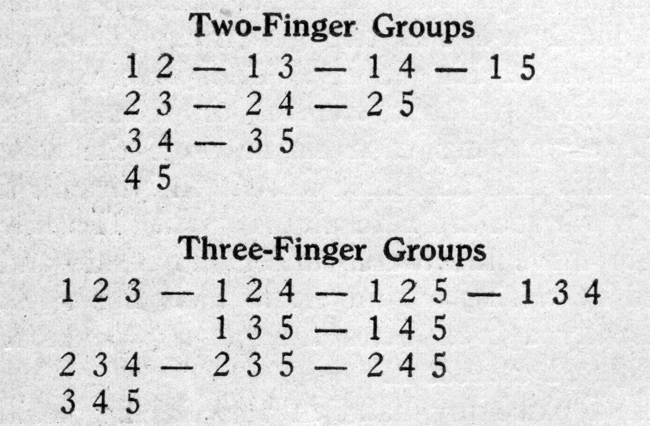

“All these exercises must be repeated with every finger of the hand, many, many times. Get the pupil interested in them and he will not be bored. How long should they be continued? Just as long as it is necessary to continue until they can be done easily and repeatedly without the slightest finger tremor. It pays to take some time in accomplishing this. Particularly, when the teacher is remaking what I call a spoiled hand, is this necessary. I have worked eight weeks in making over some hands until the tremor disappeared, before a right finger action was brought about. I have often wished, even then, that I had motion picture photographs of the pupil’s finger action that I could turn to slow motion pictures and be absolutely sure that the pupil was able to raise and lower every finger of both hands independently without the slightest tremor. This should also be done with the following finger combinations, working coordinately.

“These combinations should be done with each hand separately and then with both hands together. Extremely careful attention must be given to the matter of the elevation of the fingers playing in groups. When the fingers are raised, they should all rise to the same height or level, as observed by watching the backs of the knuckles or the first metacarpal joint. The fifth finger is very unruly. It must be raised without a ‘kick.’

“In transferring the foregoing preliminary work to the keyboard, the writer has found that these are among the very best exercises. They are, in fact, the first exercises that I use at the keyboard. The hand is placed over five convenient white keys, the weight of the hand and arm is then sustained by the thumb. There must be no rigidity. On the other hand, there cannot be what so many teachers misname—complete relaxation. If the arm is completely relaxed, the hand will fall off the keyboard by its own weight. There is nothing to stop it. On the other hand, if the arm is held so that it seems to be ‘floating in the air’ without any suggestion of nervous tension or tightness, the condition will be approximated.

“The weight is now sustained by the thumb. The hand does not seem to press the thumb down but rather to hold it resting on the key by its own weight and nothing more. The other fingers are all in playing position. The first exercise is with the second or forefinger. This descends slowly to the count ‘one,’ holds the key depressed during the counts two and three and ascends on the count four. Simple enough! Wait! Watch all of the other fingers that do not move. If they wobble around or are affected by the playing of the second finger, the exercise has not been played correctly. It is then your task to repeat this exercise an infinite number of times until you can strike with one finger with such ease, freedom and independence that none of the other fingers move. If this proves an easy task to you, you are to be congratulated. You have either been well trained or you have well articulated fingers. Ten to one, however, there will be some struggle to get this right if you are conscientious and do not ‘fool yourself.’

“It will not avail you to fool yourself. It will only lead you back to your former difficulties and obstacles. Get the exercise right or not at all. After you have trained the forefinger to a high degree of independence take the other fingers in turn and give them just as generous practice. You will not regret it. The principle is simple. There is always one sustaining finger. The playing finger must show absolutely no nervous tension, no shaking, no trembling. The fingers that do not play must not move but at the same time they must not experience the slightest stiffness or rigidity.

“YOU HAVE no idea how valuable this training is until you have gone through it. Watch the average pupil playing. There is usually no such thing as independence of fingers. If one finger moves all of the other fingers move like the branches of a tree in a high wind. Get real independence, if you want your playing ever to amount to anything. Some of the old books on technic used to seek this independence by holding the hand in a rigid position on the keys with certain notes sustained while the other fingers hammered away like a machine. This, of course, was disastrous and wrecked many a hand.

“Only a prolonged trial will convince the teacher of the enormous advantage of getting this kind of a finger control well established. As I have said, it calls for enormous patience, but the best teachers are those who possess giant patience and who have the ability to secure results through working for them and waiting for them.

“No matter what method you may employ after this, if you have established this kind of a finger control, it will surely show out in all of your work in the future.

“After all this has been accomplished, the pupil is, of course, most anxious to go to the keyboard. This is perhaps the most troublesome period, because the teacher must see to it that this condition of normal control is conferred to the piano. To insure this, continue the exercises at the table for some time.

ANOTHER good exercise at the keyboard is this. The reader has probably ‘caught on’ by this time that the up-stroke and the down-stroke are made in the same period of time and at the same speed. Both are laboriously slow and un-constrained by any nervous tension. In applying this to the keyboard, I ask the pupil to hold down five adjacent white keys by the natural weight of the relaxed arm. This is not difficult, but the teacher must be sure that the pupil is not pushing or pressing down the keys. Raise the third finger, counting four, exactly as in the table exercises, hold aloft for four counts, with the downward stroke depressing the key so that no sound of any kind is made. This is an excellent test of the very slow, properly controlled finger motion.”

Self-Test Questions on Mr. Leefson’s Article

1. What is the cause of many nervous breakdowns among musicians?

2. What is the cure?

3. What is one of the first goals in technic?

4. What is meant by independence of fingers?

5. What is the correct state of relaxation?