The Distinguished American Composer-Pianist

Mrs. H. H. A. BEACH

To say that Common Sense is the most uncommon sense that we possess, is to repeat, not only what numerous writers have expressed in language of varying intensity, but to echo the thoughts of every one of us who work out art problems of any kind. It is so easy for us to learn formulæ by heart, and then attempt to solve each question that arises, by applying some hard-and-fast rule, instead of using our common sense. This most uncommon attribute, if called into play, should teach us many things about art upon which we need to dwell. For instance, the use and abuse of technic. And by abuse I mean the application of the hard-and-fast rule on all occasions. Surely common sense would suggest that different emergencies require different action, and that one’s technical equipment in any art should be sufficiently elastic to allow free adaptation in whatever direction our tasks lead us. Especially should this be true in art which is of necessity so closely dependent upon mechanism as is the art of pianoforte playing. The instrument contains within itself so many aspects of the mere machine, that we ought continually to strive against adding further to its unyielding qualities by the imposition of a rigid technical employment of them.

To say that Common Sense is the most uncommon sense that we possess, is to repeat, not only what numerous writers have expressed in language of varying intensity, but to echo the thoughts of every one of us who work out art problems of any kind. It is so easy for us to learn formulæ by heart, and then attempt to solve each question that arises, by applying some hard-and-fast rule, instead of using our common sense. This most uncommon attribute, if called into play, should teach us many things about art upon which we need to dwell. For instance, the use and abuse of technic. And by abuse I mean the application of the hard-and-fast rule on all occasions. Surely common sense would suggest that different emergencies require different action, and that one’s technical equipment in any art should be sufficiently elastic to allow free adaptation in whatever direction our tasks lead us. Especially should this be true in art which is of necessity so closely dependent upon mechanism as is the art of pianoforte playing. The instrument contains within itself so many aspects of the mere machine, that we ought continually to strive against adding further to its unyielding qualities by the imposition of a rigid technical employment of them.

Of course, we must have technic, and plenty of it. In order to express our own thoughts, or adequately those of others, we must first acquire a sufficient command of language. This, in relation to the art of pianoforte playing, means command of technic. I hesitate to repeat the trite statement that, without adequate technic, it is absolutely impossible to express in all its fullness the meaning of any composer or composition. In the face, however, of the incompetency which so frequently meets us, it seems wise to repeat, and again repeat, the maxim that “a good workman is master of his tools.” A diligent practice of octaves, scales, trills, exercises, of whatever nature seems most’ necessary for the individual development or the correction of individual faults, a firm grounding in all the preliminary requirements of good pianoforte playing,— all these must be worked out according to the individual needs, under the guidance of some teacher gifted with “common sense.” And we have many such right here in our own country! It is not necessary to go elsewhere to find as good foundation-work as may be found in the world. Not until the pupil has reached the stage of near-virtuosity should it be found wise to leave home and home influences in search of wider culture and experience.

The Use and Abuse of Technic

Now, as to the use and abuse of technic and the hard-and-fast rule. Many times I have been asked by apparently intelligent students whether I play octaves with a loose or stiff wrist’. It always seems to me as if one should ask, “do you use a knife or a spoon in eating?” Our old friend, Common Sense, rises to explain that, in a half-dozen octave passages, each one expressing a different musical or emotional idea, precisely six kinds of octave playing would be necessary.

Again, the matter of chord-playing in passages of great force brings up several questions as to whether it is “right” to play the chords with the pressure touch, to pounce upon them from various heights above the keyboard, or apparently to throw them up in the air as if the keys were red-hot. What should Common Sense teach us about this, and all other similar problems? In order to produce perfectly even tones at great speed, how should one finger the “rheumatic scale?” (This from a pupil whose teacher recently gave me her mournful confidence.) Which fingers should we use in the trill? How much hand or arm movement should be used in playing the successive notes of a legato melody? There can be but one answer to all such questions. We must adapt the method used to each separate phrase, according to its musical and emotional significance.

I use the words “musical and emotional,” for each must have its place in our study and yet they belong together. It is only by mastering both that we succeed in eliminating the mechanical elements in pianoforte playing.

The Musical Meaning

Having acquired the technic necessary for the interpretation of whatever grade of composition we may be considering, we come, first and foremost, to the question, “What does this music mean to me?” Is it merely a placid salon-piece, or does it bring suggestions of deep earnestness or heart-rending tragedy? This is taking us into deep waters, I know, for we bring up many strange and unaccountable associations of ideas when we attempt to describe what music “means.”

The placid salon-piece generally bears its label in plain sight, and can be disposed of in few words. Usually its technical requirements are comparatively simple, and it matters little whether we employ one touch or method or another in any given passage. It is when we cross the threshold of the Temple, and enter into the atmosphere of music that has meant a part of some composer’s very life, that we must pause and search with all our faculties alert. Analyze this human document, study it over and over, from beginning to end, and try to discover what kind of message it brings us individually. If the piece appeals to us, its meaning comes out gradually under the developing fluid of our repeated analysis, until the picture takes shape, and we can then begin to think about coloring it according to our personal inclinations. Then, and only then, comes the time for attacking the technical problems with the means best adapted to the solving of each separate one.

There are so many interesting points connected with the study of a composition new to us. The developments of the main idea, its various harmonic and rhythmic changes, all the subsidiary phrases that serve to enhance its importance, where the climax occurs, (if the piece contains one) where that climax begins to work up, etc. It seems as if we should be swamped by so much that must be considered before we begin to employ technical means for the expression of musical and emotional details. A new composition resembles a picture puzzle, and sometimes seems about as unintelligible as the latter when the colored bits are tossed out onto the table. Yet we can patiently put the bits together into a cohesive whole if we confine ourselves to one difficulty at a time.

Some of us are able to read through a composition quickly, away from the instrument, as we read a book, and can thus get a good idea of the music or even learn it before taking it to the piano. There are numerous anecdotes on record about great pianists and their feats in this line. a notable one is that of Von Bülow, who, while traveling one day by railroad, studied a very difficult manuscript which he had never before seen, and, committing it to memory, played it that same evening in a concert. Naturally such feats can belong only to great musicianship, but the analysis of compositions away from the keyboard can be made a regular study with valuable practical results, and considerable ability, even in memorizing, can be acquired by patient and persistent work.

A Practical Application

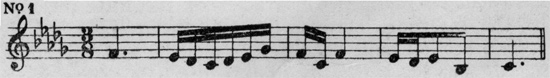

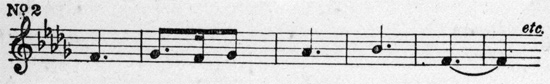

Let us take up briefly three well-known examples of modern music, differing widely in character, which may serve to illustrate many points that we have been considering. First, Rachmaninoff’s Serenade, Opus 3. At first glance this looks like a simple piece in waltz form, graceful in the outlines of its phrases and with no complicated development. No exciting climax is suggested; rather, a monotonous repetition of slight changes in the main idea. After the introductory page which merely hints at a figure of the principal subject, the Tempo di Valse begins. The theme suggests the viola in character as well as register. Indeed, perhaps we may better understand the entire piece by imagining it as written for orchestra, so suggestive is its orchestral coloring throughout. The accompaniment might be for pizzicato strings, with an occasional background of soft wind instruments. The viola theme is easily traced as it permeates the whole composition, with comparatively slight changes.

It is accompanied by a simple waltz figure played sometimes above, sometimes below the melody. The harmonic changes are strangely Oriental in their suggestiveness, and the persistent organ-point on the third and dominant seventh produces an effect of indescribable melancholy. It hints of Oriental mysteries, of indefinable longings.

I know of no instance where this latter most unusual chord-note is employed as organ-point for so long a period. Tschaikowsky’s use of the third as organ-point (Pathetic Symphony, second movement) produces a similar effect of melancholy, unrest, emotional exhaustion. Are these unusual uses of the devices of organ-point peculiar to the Russians? The question opens up interesting possibilities for discussion and comparison.

To return to our Serenade, the viola continues its mournful song, after a short codetta, in a rather more impassioned phrase, thrice repeated:

This brings us to the only suggestion of a climax that the piece contains. It is short and unimportant, for the first hopeless melancholy is at once resumed. The melody now lies in a higher octave (the oboe?) against the alto of the viola. The Serenade ends simply, with a repetition of the little codetta.

Now it may seem as if I had made “much ado about nothing” in selecting so comparatively simple a piece for minute study in piano technic, when its technical demands are apparently so slight. There is certainly nothing sensational here, but as to its being such an easy matter to bring out all the charm of this little gem of pianoforte literature, there may be several opinions. The melody gives opportunities for a singing tone of ineffable beauty and variety of color, while the accompaniment must be worked out until it is as delicate as a cobweb. As for the emotional significance of the piece, and its effect when well played, let any well equipped, sensitive pianist experiment with it and discover!

For an example of the climax and the working up to it, I know of no better instance in modern music for the pianoforte than Sgambati’s Nocturne in B minor, Opus 20. It is a bit of real Italian life, as it might be portrayed in a miniature opera. In its most impassioned moments one can almost see the tenor advance to the footlights and make his unfailing appeal to his ardent listeners. We need not enter into detailed description of this piece, another gem of rare charm, for its character is so unmistakable throughout that one could hardly go wrong in its interpretation. The contrast between its two themes is marked, and demands like contrast in the playing.

I remember that, when I had the great and often repeated happiness of playing this Nocturne in the dear old composer’s presence (some years ago in Rome), he cautioned me against playing the second theme too fast. I have among my treasures a copy of the work in which he added with his own hand several changes in harmony and dynamic marks, that he had made since it was published. I may add that the more dramatic expressiveness I put into it, the more he was pleased. Technically, its difficulties lie mainly in the production of the two kinds of singing tone demanded by the two themes, and in the forceful playing of the chords and octaves at the climax.

One more illustration, a gem which we all know and love, Brahms’ enchanting transcription of an old Scotch Lullaby in his group of pieces, Opus 117. Here again we have a singing melody, perfectly direct in its appeal, simple in its musical form. In this case, the greatest technical difficulty lies in the fact, that the melody often runs through the middle of chords, like a golden thread through beads. It must be brought out with sufficient prominence against the surrounding chord-tones, and yet it must sing. To do all this with one hand is not easy. On the emotional side, Brahms has changed the entire character of the little melody by the insertion, between its two occurrences, of a second section built on different melodic and rhythmic ideas. The black tragedy of this interlude adds a new pathos to what at first seemed a simple lullaby of rather placid character. When this returns, although the notes remain the same, it is hard to recognize it as the same melody. It has become intensified by passing through the valley of the shadow, until it glows with a deep spiritual radiance.

Now what has technic to do with all this? Everything. These three pieces, none of them demanding great virtuosity, must be played with as different a touch as if we played them on three kinds of instruments. Each one has its own story to tell, and the technic must be suited to the telling. Here we come to the real value of technic: a means of expression.

How often do we hear a comparatively simple composition so buried beneath the avalanche of a stupendous technical display, under the hands of some virtuoso king, that its true character vanishes!

If technical command be analogous to command of language, we are here reminded that “language is given to conceal thought.” Many pianists might study, to their inestimable benefit, the interpretation of songs as given by the greatest singers in the recital programs of to-day. Each song is a complete drama, be it ever so small or light in character, and no two are interpreted in the same way. Even the quality of the voice may change absolutely, in order to bring out some salient characteristic of the composition. Technical perfection may indeed be there, but so completely subordinated to the emotional character of the song that we lose all consciousness of its existence.

Adapting the Means to the End

It is this power of adapting means to ends, that distinguishes the greatest pianists in like degree. The ability to make each piano piece, whether a master sonata or a simple nocturne, into a life-drama carrying the hearer along a torrent of emotional intensity while the brief story unfolds itself, belongs only to the very greatest among them. Who thinks of the technic while De Pachmann plays a Chopin Mazurka? He may be doing wonderful things in touch and technical detail., but it is our hearts that respond to each motion of his hands. Imagine stopping to consider technic when D’Albert plays a Beethoven sonata, or Gabrilowitsch the G major conerto, (sic) Carreño the Emperor, or Paderewski—anything when he is at his best!

Technic is like most of the important things in life; a power for good or evil. It must be the servant, not the master, of our musical equipment, ready to respond at all times to whatever demands we make on it, and equally ready to illustrate the idea that the greatest art conceals art. If we play each musical composition in such a way as to make it a well-rounded entity, symmetrical, fully developed and beautifully colored, we shall do much toward removing the stigma cast upon the pianoforte as merely a mechanical instrument. And if we bring out the emotional side of that composition in such a way as to make it tell a story, we shall do even more. Do we pianists like to hear people say “No, I never go to piano recitals. They are so monotonous that they bore me to death?” Then let us make every effort to play music that is not monotonous with so much expressiveness that each piece sings; with a due regard to the proper arrangement of our programs so that every work may be “hung on the line” and yet not “kill” its neighbor. Our noble instrument with its marvelously rich literature, will respond bravely to our love and devotion, and exercise its real power over its hearers, whether we play octaves with a loose wrist, or not!