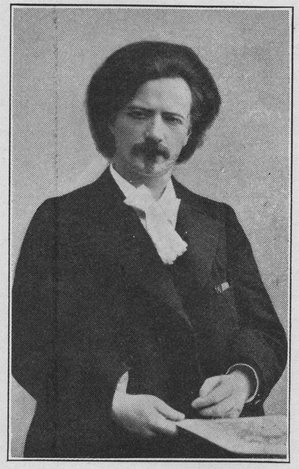

Excepting only Frédèric Chopin, no character in musical history has been so prominently identified with Poland as Ignace Jan Paderewski. Considered from a popular standpoint, Chopin never attained that wide celebrity which attaches to the great Polish virtuoso of the present day, whose fame has reached millions who may never hear him play, but are as familiar with his name as that of the greatest statesman of the day. Moreover, Paderewski is wholly of Polish origin while Chopin’s attraction to France through ancestry and long residence need not be commented upon.

Properly to appreciate the life and ideals of Paderewski it is desirable to refresh one’s memory regarding the remarkable country of his birth, for while Paderewski has shown his wide cosmopolitan experience in his compositions he is nevertheless a most devoted patriot of his native land.

Patriotism it is that binds American sympathies to Poland. The services of the Polish patriot Thaddeus Kosciuszko in our own Revolutionary War will never be forgotten in the new world. But even the zeal and skill of men like Kosciuszko were not able to save their country from the intrusion of the armies of more powerful countries.

In the third quarter of the XVI century, Polish rule extended over some 380,000 square miles—a territory greater than that occupied by all of our New England states and our Middle Atlantic states, with the addition of Ohio, Indiana and Illinois. Now, there is no Poland save in the hearts of the Polish people. What was once a great country of thirty-five million people is now tragically divided into provinces of Russia, Prussia and Austria; three-quarters of Poland’s former possessions went to Russia.

Despite every imaginable effort on the part of the governments to exterminate patriotism in what was once Poland, the Poles of to-day, who have politically ceased to be a nation for one hundred years, find the love of country burning fiercer in their hearts than ever before. They have witnessed the genius of their great sons and daughters winning fame in all lands while their own soil has been under the heel of the despot. The revolutions of the forties and the sixties failed to bring liberty to Poland despite the intervention of France and Great Britain ; three-fourths of Poland paid dearly for her revolutions for Russia seized members of the aristocracy and hurried them off to Siberia like felons.

Nevertheless, proud hearts still beat firm and strong, waiting for the day when Fate will bring back the old glory of the desecrated land.

POLISH HISTORY AND CULTURE.

Polish history may be traced back to origins so remote as to be largely mythological. In the sixteenth century it was the most powerful country of eastern Europe. In this land of valiant knights and brilliant women, aristocracy flourished. The warring interests of these nobles resulted for a time in breaking the unity necessary for the preservation of military force and this contributed to the downfall of Poland.

It is estimated that over fifteen million people still speak the Polish language; Polish literature dates from antique poems said to have been produced in the tenth century. Doubtless the Polish writers best known in countries beyond the borders of Poland are Mickiewicz, Slowacki, Krasinski and Henryk Sienkiewicz. Those who have read the masterpieces of the last named writer (Pan Michael and With Fire and Sword) may estimate the depth and power of Polish literary attainments.

A GENERAL ASPECT OF POLISH MUSIC.

Polish music is strongly characteristic in its national tendencies. At first religious and then moulded after the folk dances and folk songs of the people, it is very intimately interwoven with the everyday life of the men and women of all stations. The polonaise of the court is as national in its spirit as the mazurka of the peasant. Among those who did much to preserve the beautiful in Polish

Folk Music, was Eisner, the teacher of Frédèric Chopin. Chopin’s own part in introducing the charm of Polish melodies and rhythm to the musical world is well known to all cogniscenti. Another significant worker in Polish musical development of the past was Stanislaus, who, although born in Lithuania (1820), is chiefly known for his devotion to Polish musical ideals.

PADEREWSKI’S ANCESTRY AND EARLY YEARS.

Paderewski’s father was a gentleman farmer in Kurylówka (Podolia). Podolia is now a province of South West Russia. His mother was known to have been a woman of exceptional musical gifts but as she died when the boy was still very young he received no benefit from this source.

Paderewski was born at his father’s homestead, November 6, 1860. When he was three years old his father was exiled to Siberia for suspected connection with a revolutionary project. When the exile returned after feeling the iron hand of Russian despotism, it may be imagined that nothing was left undone to instill a love for Poland in the heart of the fair-haired little boy. During his father’s absence the little orphan did not receive nearly so much musical education in his early childhood as the average child of to-day. His musical tendencies, however, were very manifest. It is said that when he was little more than an infant, he clambered up to reach the piano keyboard and produce beautiful tones. Another story has it that an itinerant fiddler took an interest in the obvious talent of the child and gave him a few lessons now and then. His next teacher was one who visited the farm at intervals of one month and taught the boy operatic arrangements of a semi-popular type.

At the age of twelve, Paderewski was sent to Warsaw where he entered the conservatory as a regular student. His piano teacher there was Janotha. Janotha was an excellent routine teacher with some inspirational force. Janotha’s daughter, Nathalie, later a pupil of Mme. Clara Schumann, also became a pianist of great note in Europe. Raguski, Paderewski’s teacher in Harmony at the Warsaw Conservatory, is little known outside of Poland.

The early ambition of the future virtuoso was not that of becoming a great pianist, but rather that of becoming a great composer. It was with this purpose in view that at his early concerts he often played his own compositions. One instance pertaining to his early work as a pianist, is very interesting. He was engaged to play at a concert in a little rural music centre and found the piano so antiquated that the hammers persisted in staying away from the strings after they were struck. In order to give the concert he hired a man with a switch, who adjusted these hammers after they were struck as the program proceeded. This was probably the first piano ever introduced with a partly human action. Paderewski re-entered the conservatory at Warsaw and when he was only eighteen years of age his proficiency was so pronounced that he was appointed a teacher in the institution. By this time he had married a Polish girl, and when he was only nineteen, the great tragedy of his life came with the death of his wife, leaving him with a son bright in mind but paralyzed in body. To this son Paderewski became the most devoted of fathers and although the boy died in youth, the great pianist was wrapped up in his life as in his own.

PADEREWSKI AS A CONSERVATORY TEACHER.

One has but to imagine what the effect of the routine life of the Conservatory was upon so sensitive a nature as that of the young Paderewski. From early morning to late at night he taught with little intermission. This was a kind of serfdom to a man with Paderewski’s temperament. His great desire was still that of devoting himself to musical composition. It was then that he resolved to become a virtuoso in order that he might later have the leisure to become a composer. He determined to go to Leschetizky at Vienna, but stopped on the way in order to study composition with Kiel and Urban at Berlin. Kiel was one of the most renowned teachers of counterpoint of his day and was professor of composition at the Royal High School of Music. Heinrich Urban was the teacher of composition at Kullak’s famous Academy. At the age of twenty-three Paderewski received the appointment of pianoforte teacher at the Strasburg Conservatory where his monthly income was so insignificant that most American teachers would have turned up their noses at it.

INSPIRATION FROM A FAMOUS ACTRESS.

It was while he was at Strasburg that Paderewski met his famous compatriot, Mme. Modjeska (Mme. Modrejewska). This distinguished artist’s father had been a musician and she immediately took an interest in the artistic career of the young man with such great ambition and high ideals. Herself one of the greatest of Shakesperian actresses of the time, she was able to give the young man advice of a practical nature which he was only too glad to accept. She found in him a “polished and genial companion; a man of wide culture; of witty and sometimes biting tongue; brilliant in table talk; a man wide awake in all matters of personal interest, who knew and understood the world, but whose intimacy she and her husband especially prized for the elevation of his character and refinement of his mind.”

WITH LESCHETIZKY.

When he was twenty-six years of age, Paderewski, encouraged by Mme. Modjeska, found himself in Vienna under the guidance of Prof. Theodore Leschetizky and his equally renowned wife, Mme. Annette Essipoff (Essipova). This was in 1886 when Leschetizky was then fifty-six years of age and had been teaching for forty years, as he began when he was only fifteen years of age. Leschetizky was what can only be described as a natural teacher. Where Paderewski had found teaching in a conservatory galling to him, Leschetizky found it his life work. Indeed he taught in the St. Petersburg Conservatory for over twenty-five years.

Leschetizky’s wide experience extended from the day of his own teacher Czerny through that of his contemporaries up to the present. Naturally he took an immense interest in his fellow countryman, Paderewski, who remained his pupil for the better part of four years.

Paderewski, it should be remembered, was an accomplished musician when he went to Leschetizky. He had already made a tour of part of Russia and had been engaged in teaching advanced pupils for several years. It was this spirit of ambition to do better and still better which led the brilliant young musician to a realization of his shortcomings and the necessity for more study.

At the end of his first year with Leschetizky, Paderewski appeared in concert in Vienna and caused an immediate sensation. At the time the tendency was to attribute his great success to the special methods of Leschetizky. As a matter of fact, Leschetizky has often denied that he has any method except that employed by his Vorbereiter in removing the technical shortcomings of mature pianists whose previous training has been more or less irregular. Leschetizky himself has never posed as anything other than an artist teacher employing any justifiable means to reach a given end. In the case of Paderewski, he had wonderful material with which to work as there can be no question that Paderewski would have been a great virtuoso irrespective of who might have been his teacher.

IN PARIS AND LONDON.

Paderewski’s first recital at the Salle Erard in Paris (1888) was attended by a very slender audience. Fortunately the great orchestral conductors Colonne and Lamoureux were present and realized at once that a master pianist had appeared upon the horizon. They engaged him immediately for important orchestral concerts and almost before he knew it, the artist who had waited so long and worked so hard for success was the lion of the hour in Paris. A later appearance at the Conservatoire established him as one of the great pianists of the day—the compeer of Liszt and Rubinstein.

London, like Paris, was a trifle apathetic at first but Paderewski soon became the idol of the hour in England, and has since been enormously popular with both the public and the musicians. The attitude of the conservative English critics of the time was doubtless influenced by the sensational manner in which Paderewski had been received in Paris and by the constant reference to his manner of wearing his hair, a matter due to his own taste and not to an attempt to secure publicity. The pianist formed the habit of not reading criticism of his playing or his personality whether favorable or unfavorable, and went calmly along the even tenor of his way, letting the critics fight among themselves as to his ability.

DEBUT IN AMERICA.

Paderewski’s American debut was made November 17, 1891, in New York. His first audience was representative and brilliant but here again most of the critics were loath to accept the famous pianist at his real artistic worth. The public, however, found his playing so remarkable that his success grew “like an avalanche.”

Here was a pianist with high artistic ideals, abundant technic, who could speak to his audience through the keyboard so that they would find a newer and richer meaning in the messages of the masters. His consequent success in America is now a part of our musical history. While this has often been estimated in huge sums of money, such a criterion is perhaps unfair to American musical audiences and American musical standards. It is better to say that people actually went hundreds of miles in order to be present at his recitals. Not even Rubinstein was received with such astonishing favor.

IN GERMANY.

Probably no pianist had more difficulty in breaking through conventions in Germany than had Paderewski. It seemed a part of the German musical life to condemn any attempt to avoid the stereotyped in technical methods. Indeed, when Paderewski played in Berlin, he followed the performance of his own remarkable concerto by an encore from Chopin. Von Bülow, it is said, was so disgruntled at the ovation given to the Polish pianist that he showed his feeling by sneezing violently during the encore. The unsympathetic attitude of a few carping critics of the “Vaterland” affected the pianist so greatly that he refused to appear in Germany for some years. When he did appear, however, the public ovation given to him was exceptional in every way.

PADEREWSKI AS A PIANIST.

If one were asked to define Paderewski’s greatness as a pianist, the best phrase to employ would doubtless be, “It is because his grasp of his art is all-comprehensive.” One does not speak of “the technic of Paderewski,” the “pedaling of Paderewski,” the “bravoura of Paderewski,” as all these: and other characteristics are merged into his art so that no one feature of his work at the keyboard outshadows any other. Perhaps one of the most intelligent of all appreciations is that of Dr. William Mason, who knew the pianist intimately, and was in turn greatly admired by Paderewski. Dr. Mason writes “The heartfelt sincerity of the man is noticeable in all that he does, and his intensity of utterance easily accounts for the strong hold he has over his audiences. Paderewski’s playing presents the beautiful contour of a living vital organism. It possesses that subtle quality expressed in some measure by the German word Sehnsucht and in English as intensity of aspiration. This quality Chopin had and Liszt frequently spoke of it. It is the undefinable poetic haze with which Paderewski invests and surrounds all that he plays that renders him so unique.”

PADEREWSKI THE COMPOSER.

Mr. Henry T. Finck, an intimate of Paderewski, in his excellent brochure Paderewski and His Art (now unfortunately out of print), makes the following statement: “Of Paderewski it must be said as of Chopin, Liszt and Rubinstein, that great as is his skill as a pianist, his creative power is even more remarkable. Although he is a Pole and Chopin his idol, yet his music is not an echo of Chopin’s.” It has been noted that Paderewski’s first ambition was to become a composer; his whole life work has in fact been focused upon this firm desire. He became a pianist in order that he might purchase the leisure for composition. However, there can be no doubt that his epoch-making success as a virtuoso has so colored the public mind that it refuses to consider the master works of Paderewski while it readily admits those of less worthy composers not afflicted with a great reputation as a performer. Serious-minded musicians who have become intimately acquainted with Paderewski’s compositions for orchestra, the stage, the voice, the piano, etc., do not hesitate to declare him not only among the foremost musical creators of the present, but among the great masters of all times.

The little Minuet in G, known as “Paderewski’s Minuet,” although a bagatelle, is probably one of the five most popular pieces ever written, yet very few of Paderewski’s other more noteworthy piano pieces are widely known. His concerto for piano and orchestra is one of the finest works of its description and readily ranks with the great concertos of Chopin, Beethoven and Brahms, The Chants du Voyageur are extremely melodious and full of character. Many of the piano pieces in the set known as Six Humoresques de Concert, particularly the Caprice in the Style of Scarlatti and the Burleska, are singularly distinctive and interesting. The Burleska has a “bite” to it which makes, it one of the most fascinating piano pieces of its class. The Toccata Dans le Désert is full of atmosphere, but demands a very skillful interpreter to bring out its full meaning. Of the four Morceaux—Légende, Mélodie, Theme Varié in A and Nocturne in B Flat, the last named is possibly the most played. The Concerto for piano and orchestra in A minor is easily one of the greatest works in larger forms written for piano. One critic has rated it as the greatest concerto since Schumann. Paderewski’s songs are rich and full of character while always sincere in their delineation of the poet’s thought. His Symphony in B minor, which first became known in the United States through the fine performances of it given by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, is a work of majestic lines, magnificently orchestrated and filled with the great composer’s splendid melodic ideas and harmonic treatment. It is said that he has written the woes of his native land into this masterpiece. His opera Manru should be heard more frequently as many concede it to be Paderewski’s finest production. This opera was first given at the Court Theatre in Dresden in 1901. The libretto is by Paderewski’s gifted friend Alfred Nossig. The plot deals with a gypsy subject. The orchestration of this work is exceptionally powerful but always appropriate. The Polish Fantasia for piano and orchestra is widely admired, and some concede to this the place of first honor among Paderewski’s compositions; wherever the pianist has played this original and characteristic work it has always produced a furore.

PADEREWSKI’S PHILANTHROPIES.

Paderewski has given lavishly of the wealth bestowed upon him by enthusiastic music lovers. Upon one occasion when he had promised his services for a benefit to be held for the Actor’s Fund in America, he found that he was unable to come. He promptly sent his check for $1,000, explaining that he was physically incapacitated. His best known philanthropy in America is the Paderewski Fund, consisting of the sum of $10,000 to be devoted to the purpose of fostering musical composition in America. Once every three years a prize of about $500 is given to some fortunate competitor. Among those who have succeeded thus far have been Henry K. Hadley, Horatio W. Parker, Arthur Bird and Arthur Shepard. The fund was founded in 1900, and is a very gratifying evidence of Paderewski’s interest in American musical development.

PADEREWSKI’S PERSONALITY.

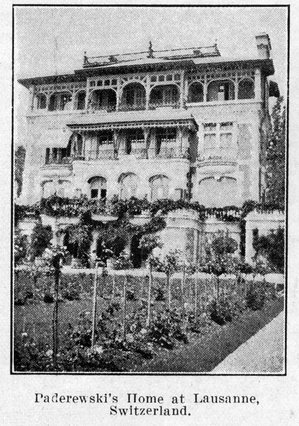

The philanthropies of Paderewski represent an interesting side of his nature. His intense seriousness at times makes it difficult to believe that he may be the most youthful and vivacious of men. His friends are well aware of his quick wit as well as his broad general learning. Linguistically speaking, his accomplishments are very exceptional even for a Pole. He speaks English, for instance, with so slight a suggestion of an accent that it is not noticeable. Paderewski’s magnetism, has been the subject of many discussions. His fascinating personality, his breadth of vision and his lofty idealism are well remembered by all who have known him. At his beautiful home at Merges, Switzerland, he takes great delight in horticultural and agricultural matters and is joined in this by his accomplished wife whom he married in 1898 and who for years cared for his invalid son. Mme. Paderewski was born in Barrone Rosen. Her first husband was the noted Polish violinist, Lodislas Gorski.

A PADEREWSKI PROGRAM.

In the preparation of the following list the main considerations have been general musical interest and not too great difficulty. Paderewski possesses a remarkable sense of appropriateness. His orchestral compositions, unlike the few essays of Chopin, are real orchestral works, and his pianoforte compositions, unlike many of Beethoven’s piano pieces, are always idiomatically pianistic. Many of his works, however, are so far beyond the ability of the average performer that we can not list them in a program like the following.

Piano Solos Grade

Mazurka. Op. 9 (Book II), No. IV ……… 5

Krakowiak. Op. 9 (Book II), No. V ……. 6

Polonaise. Op. 9 (Book II), No. VI ……… 7

Burlesque. Op. 14, No. 4 ……… 7

Au Soir. Op. 10, No. 1 …………… 4

6 Menuet in G. Op. 14, No. 1 ……… 8

Barcarolle. Op. 10, No, 4 ……… 5

Cracovienne, Op. 14, No. 6 ……… 6

Chant du Voyageur ……… 5

Chant d’Amour. Op. 14, No. 2 ……… 4

Legende No. 2 ……… 8

Legende. Op. 10, No. 1 ……… 6

Scherzino. Op. 10, No. 3 ……… 5

Nocturne. Op. 10, No. 4 ……… 4

Music lovers desiring to study a more difficult type of composition will find in the Variations and Fugue in A Minor and in the Sonata, Op. 21, modern pianoforte works which should be in the repertoire of every very advanced pianist.

BOOKS ON PADEREWSKI.

Of the biographies and appreciations of Paderewski, probably the best that have ever been written are those of Henry T, Finck (out of print), Edward A. Baughan and Alfred Nossig. There is an excellent life in Polish by Opienski, the noted Polish critic.